It is the world’s largest contiguous mangrove forest, with the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve spread over more than 10,000 square kilometres. Within its labyrinth of channels and creeks are numerous islands that appear and disappear with the tides.

Sundarbans literally means “beautiful forest”. It’s an appropriate name for these deep, impenetrable forests that harbour and hide an astonishing diversity of species, including endangered Gangetic and Irrawaddy dolphins, northern river terrapins, and royal Bengal tigers.

Additionally, over four million humans inhabit this vast landscape. The mangroves provide them with livelihoods and protection from catastrophic weather like cyclones, but they are also a source of fear and danger.

Wildlife photographer Dhritiman Mukherjee has been travelling to the Sundarbans since the year 2000 and has made over 60 trips there. During one of his early trips, collecting data on bird and mangrove species, he became fascinated with the diversity of species in the Sundarbans and felt the need to document and draw attention to it. He was charmed by the various mangrove species and their ability to survive in adverse conditions and the plethora of wildlife hidden within this habitat. “The Sundarbans is a difficult place to explore and experience,” he says.

With a selection of his photographs, Dhritiman takes us on a journey through the Sundarbans and then circles back to why photography is an important tool for its conservation.

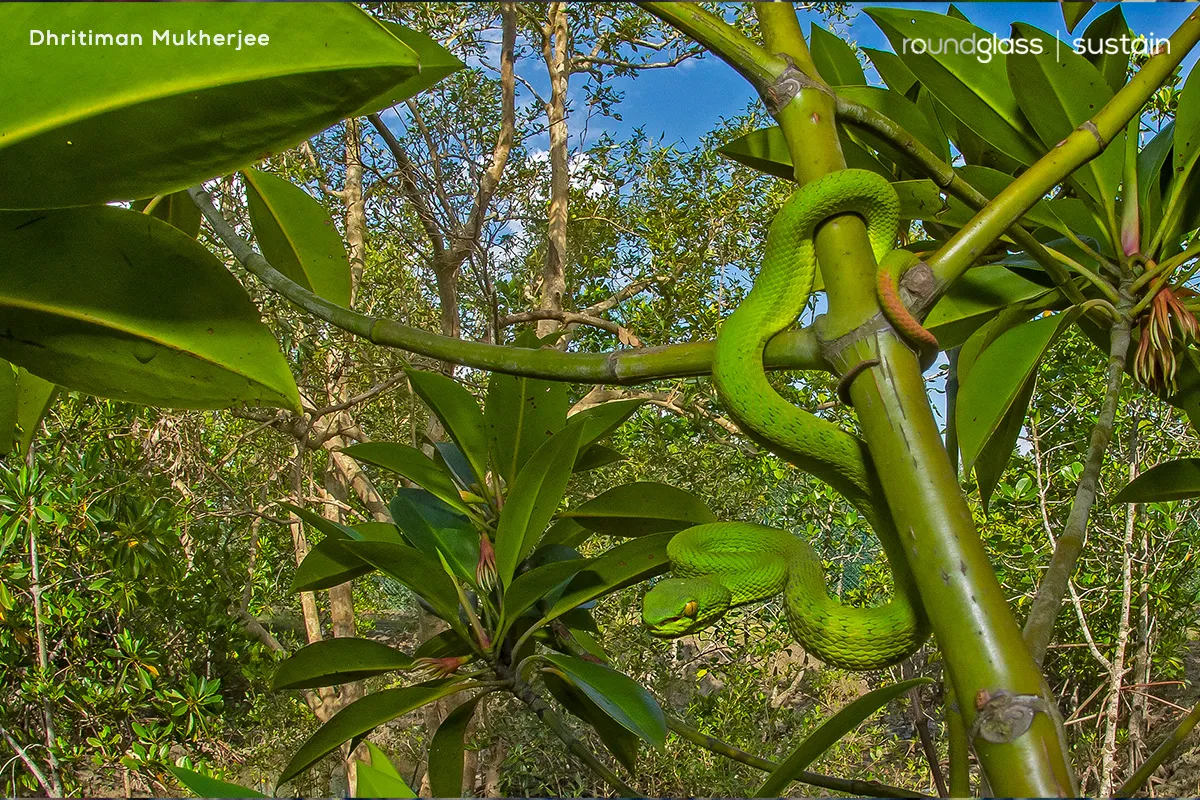

Though it is most popularly considered the Bengal tiger’s habitat, the Sundarbans forest also has plenty of other wildlife, including chitals, wild boars, fishing cats, rhesus macaques, leopard cats, Indian grey mongooses and otters. Saltwater crocodiles and water monitor lizards are also commonly sighted, and while snakes like the Indian python and king cobra exist, they are rarely seen. The Sundarbans is a favourite among birders too, for its abundance of kingfishers, raptors, shorebirds, and migratory birds.

This biodiversity hotspot harbours over 50 species of mammals, 315 species of birds, and 59 species of reptiles within its mangrove forests. And while sighting the elusive Sundarbans tiger is undoubtedly exciting, spotting and photographing more diminutive creatures brings Dhritiman just as much joy. “Thrilling subjects and species, like the tiger, do attract more people, but all species have a role to play in the Sundarbans ecosystem,” he says.

The Sundarbans forest can be hauntingly still, but as the tide recedes and sandy shores rise out of the green waters, the landscape comes alive. When mangrove roots emerge from under brackish water at low tide, the oddest creatures crawl out. Mudskippers hop out of the water and walk on land. A male fiddler crab waves its large claw to attract females. Watchful kingfishers perch on branches that lean into the water. Saltwater crocodiles bask in the sun while water monitors swagger along sandbanks. These aquatic, terrestrial, and intertidal critters work very closely with the mangrove ecosystem and help keep it running efficiently.

Crabs, for instance, are essential to the mangrove ecosystem. They are efficient burrowers who pierce holes and aerate the compact oxygen-starved soil, benefitting the mangroves. Their activity of reshuffling layers of clay and sediment helps nutrient transfers among various layers. Because of these contributions, they are often called ecosystem engineers. Hermit crabs are intriguing creatures found in this estuarine habitat. They select the empty shells of molluscs like Telescopium to protect themselves from predators.

Some male fiddlers stand beside their burrows and vigorously wave an enormous claw to attract a wandering female. Once a prospective mate is charmed, the male will lead her underground into his burrow.

Not much is known about other small creatures that thrive in the Sundarbans. Numerous kinds of molluscs inhabit tidal flats and backwater inlets and can be spotted during low tide. When the tide rises, they may appear on tree trunks. These include gastropods such as Telescopium, the cone-shaped sea snails seen in the background above.

The tissues of their skin, gills, and digestive system can absorb and accumulate toxic chemicals (pollution) emitted from various sources in the intertidal environment. This is why they are considered potential bio-indicators of mangrove forests and coastal waters, i.e. they reveal the pollution levels of this habitat.

Numerous species of snakes are found in the Sundarbans, including red-tailed pit vipers, Russell’s vipers, common kraits, and a host of sea snakes like dog-faced water snakes and hook-nosed sea snakes. Though the Indian python also lives in the Sundarbans, it is rarely spotted. The snake population of this region is on the decline now because villagers resort to retaliatory killing when a snake bites and kills someone.

Like many forest communities, the residents of the Sundarbans have a complex relationship with their habitat. The mangroves provide them with livelihoods and protection from weather events like cyclones, but they also recognise that they can be dangerous. Forest communities rely on this habitat for food, timber, firewood, traditional medicine, and means of livelihood such as fishing, crab-catching, and honey collection. Because of the nature of their jobs, the Sundarbans honey gatherers know this forest intimately. They enter the intertidal forests between April and June when fishing is prohibited. In addition to navigating the maze-like mangroves, they must leave the safety of their boats, harvest honey from beehives, and make their way back home — knowing fully well that they are in prime tiger territory.

The honey gatherers of the Sundarbans (known as mouli or moule) have a deep understanding of the forest gained from firsthand observation of their environment and knowledge passed down the generations. They are intrinsically connected to the natural processes that surround them. For the duration of their honey gathering expedition, they eat and sleep on their boats, which they stock with the basics they will need, such as food, fuel, potable water, and the tools of their trade.

Before entering the forest, every mouli seeks the blessings of Bonbibi, the revered jungle deity of the people of the Sundarbans, believed to protect them from the dangers of the forest, especially the tiger.

Bonbibi literally means “Mother Nature”. Before any expedition sets off into the forest, the group of honey gatherers create a makeshift shrine, make offerings, and pray.

The photographs of the Sundarbans you see above represent just a tiny fraction of the scope and depth of Dhritiman’s journey as a wildlife photographer. “My photography started as something fun, but it became more meaningful and a great pleasure when I realised I could contribute to society,” he says.

The story of the Sundarbans has many lessons for all of us.

A tiny number; some biologists, photographers, conservationists, and scientists. And, of course, the indigenous and forest communities that live on the fringes of so-called civilisation.

As Ambassador of the Mangrove Photography Awards, Dhritiman offers aspiring photographers of the wild some direction and perspective. He believes that a photographer’s role is to show photos of the natural world to those disconnected from it. Those who have never seen a mangrove forest must feel inspired and intrigued by these images. If it gives them pleasure, it might also raise their awareness of the natural world and the need to preserve it. It’s essential to make those connections between a great image and the need to preserve the subject, and that’s where photography comes in. It is like bait, creating visual interest for people and connecting them to the subject through emotion, new information, a critical issue or scientific explanation. “A visual connection can spark interest among more people. Surprise brings pleasure because it is new knowledge. It kindles curiosity, and that leads to engagement,” says Dhritiman.

His advice to aspiring wildlife photographers is simple. “Do your homework on a particular place, the habitat, the species you may encounter. Prepare yourself for the space you are entering. Let your observations be a contribution to society,” he emphasises. He adds that in every sphere of life, it is important to contribute and not only focus on competing. “It is the same with these Mangrove Photography Awards. When we showcase the different mangroves and mangrove ecosystems from different countries, we highlight their importance and problems. The goal is to popularise and create an understanding of the magnificent ecological role mangroves play in our lives, even if we reside thousands of miles away from them. That’s how everyone who participates in this contest contributes to the conservation of these constantly changing ecosystems.”